Gravitational redshift

In astrophysics, gravitational redshift or Einstein shift describes light or other forms of electromagnetic radiation of certain wavelengths that originate from a source that is in a region of a stronger gravitational field (and that could be said to have climbed "uphill" out of a gravity well) that appear to be of longer wavelength, or redshifted, when seen or received by an observer who is in a region of a weaker gravitational field. If applied to optical wavelengths this manifests itself as a change in the colour of the light as the wavelength is shifted toward the red part of the light spectrum. This means that the light is less energetic, longer in wavelength, and lower in frequency.

Spectral lines found in the observed light will also be shifted toward the longer wavelengths or "red" end of the spectrum. This shift can be observed along the entire electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to gamma rays.

Electromagnetic radiation that has passed "downhill" into a gravity well (a region of stronger gravity) shows a corresponding increase in energy, shorter wavelength, higher frequency and is said to be gravitationally blueshifted.

Contents |

Definition

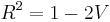

Redshift is often denoted with the dimensionless variable  , defined as the fractional change of the wavelength[1]

, defined as the fractional change of the wavelength[1]

Where  is the wavelength of the electromagnetic radiation (photon) as measured by the observer.

is the wavelength of the electromagnetic radiation (photon) as measured by the observer.  is the wavelength of the electromagnetic radiation (photon) when measured at the source of emission.

is the wavelength of the electromagnetic radiation (photon) when measured at the source of emission.

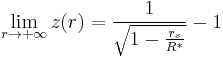

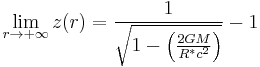

The gravitational redshift of a photon can be calculated in the framework of General Relativity (using the Schwarzschild metric) as

with the Schwarzschild radius

,

,

where  denotes Newton's gravitational constant,

denotes Newton's gravitational constant,  the mass of the gravitating body,

the mass of the gravitating body,  the speed of light, and

the speed of light, and  the distance between the center of mass of the gravitating body and the point at which the photon is emitted. The redshift is evaluated in at a distance in the limit going to infinity. This formula only makes sense when

the distance between the center of mass of the gravitating body and the point at which the photon is emitted. The redshift is evaluated in at a distance in the limit going to infinity. This formula only makes sense when  is at least as large as

is at least as large as  . When the photon is emitted at a distance equal to the Schwarzschild radius, the redshift will be infinitely large. When the photon is emitted at an infinitely large distance, there is no redshift. The redshift is not defined for photons emitted inside the Scharzschild radius. This is because the gravitational force is too large and the photon cannot escape.

. When the photon is emitted at a distance equal to the Schwarzschild radius, the redshift will be infinitely large. When the photon is emitted at an infinitely large distance, there is no redshift. The redshift is not defined for photons emitted inside the Scharzschild radius. This is because the gravitational force is too large and the photon cannot escape.

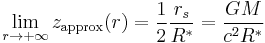

In the Newtonian limit, i.e. when  is sufficiently large compared to the Schwarzschild radius

is sufficiently large compared to the Schwarzschild radius  , the redshift becomes

, the redshift becomes

History

The gravitational weakening of light from high-gravity stars was predicted by John Michell in 1783 and Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1796, using Isaac Newton's concept of light corpuscles (see: emission theory) and who predicted that some stars would have a gravity so strong that light would not be able to escape. The effect of gravity on light was then explored by Johann Georg von Soldner (1801), who calculated the amount of deflection of a light ray by the sun, arriving at the Newtonian answer which is half the value predicted by general relativity. All of this early work assumed that light could slow down and fall, which was inconsistent with the modern understanding of light waves.

Once it became accepted that light is an electromagnetic wave, it was clear that the frequency of light should not change from place to place, since waves from a source with a fixed frequency keep the same frequency everywhere. One way around this conclusion would be if time itself was altered—if clocks at different points had different rates.

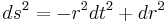

This was precisely Einstein's conclusion in 1911. He considered an accelerating box, and noted that according to the special theory of relativity, the clock rate at the bottom of the box was slower than the clock rate at the top. Nowadays, this can be easily shown in accelerated coordinates. The metric tensor in units where the speed of light is one is:

and for an observer at a constant value of r, the rate at which a clock ticks, R(r), is the square root of the time coefficient, R(r)=r. The acceleration at position r is equal to the curvature of the hyperbola at fixed r, and like the curvature of the nested circles in polar coordinates, it is equal to 1/r.

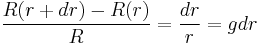

So at a fixed value of g, the fractional rate of change of the clock-rate, the percentage change in the ticking at the top of an accelerating box vs at the bottom, is:

The rate is faster at larger values of R, away from the apparent direction of acceleration. The rate is zero at r=0, which is the location of the acceleration horizon.

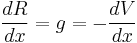

Using the principle of equivalence, Einstein concluded that the same thing holds in any gravitational field, that the rate of clocks R at different heights was altered according to the gravitational field g. When g is slowly varying, it gives the fractional rate of change of the ticking rate. If the ticking rate is everywhere almost this same, the fractional rate of change is the same as the absolute rate of change, so that:

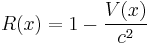

Since the rate of clocks and the gravitational potential have the same derivative, they are the same up to a constant. The constant is chosen to make the clock rate at infinity equal to 1. Since the gravitational potential is zero at infinity:

where the speed of light has been restored to make the gravitational potential dimensionless.

The coefficient of the  in the metric tensor is the square of the clock rate, which for small values of the potential is given by keeping only the linear term:

in the metric tensor is the square of the clock rate, which for small values of the potential is given by keeping only the linear term:

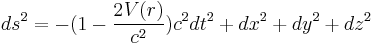

and the full metric tensor is:

where again the c's have been restored. This expression is correct in the full theory of general relativity, to lowest order in the gravitational field, and ignoring the variation of the space-space and space-time components of the metric tensor, which only affect fast moving objects.

Using this approximation, Einstein reproduced the incorrect Newtonian value for the deflection of light in 1909. But since a light beam is a fast moving object, the space-space components contribute too. After constructing the full theory of general relativity in 1916, Einstein solved for the space-space components in a post-Newtonian approximation, and calculated the correct amount of light deflection – double the Newtonian value. Einstein's prediction was confirmed by many experiments, starting with Arthur Eddington's 1919 solar eclipse expedition.

The changing rates of clocks allowed Einstein to conclude that light waves change frequency as they move, and the frequency/energy relationship for photons allowed him to see that this was best interpreted as the effect of the gravitational field on the mass–energy of the photon. To calculate the changes in frequency in a nearly static gravitational field, only the time component of the metric tensor is important, and the lowest order approximation is accurate enough for ordinary stars and planets, which are much bigger than their Schwartzschild radius.

Important things to stress

- The receiving end of the light transmission must be located at a higher gravitational potential in order for gravitational redshift to be observed. In other words, the observer must be standing "uphill" from the source. If the observer is at a lower gravitational potential than the source, a gravitational blueshift can be observed instead.

- Tests done by many universities continue to support the existence of gravitational redshift.[2]

- Gravitational redshift is not only predicted by general relativity. Other theories of gravitation require gravitational redshift, although their detailed explanations for why it appears vary. (Any theory that includes conservation of energy and mass–energy equivalence must include gravitational redshift.)

- Gravitational redshift does not assume the Schwarzschild metric solution to Einstein's field equation – in which the variable

cannot represent the mass of any rotating or charged body.

cannot represent the mass of any rotating or charged body.

Initial verification

A number of experimenters initially claimed to have identified the effect using astronomical measurements, and the effect was eventually considered to have been finally identified in the spectral lines of the star Sirius B by W.S. Adams in 1925. However, measurements of the effect before the 1960s have been critiqued by (e.g., by C.M. Will), and the effect is now considered to have been definitively verified by the experiments of Pound, Rebka and Snider between 1959 and 1965.

The Pound–Rebka experiment of 1959 measured the gravitational redshift in spectral lines using a terrestrial 57Fe gamma source. This was documented by scientists of the Lyman Laboratory of Physics at Harvard University. A commonly cited experimental verification is the Pound–Snider experiment of 1965.

More information can be seen at Tests of general relativity.

Application

Gravitational redshift is studied in many areas of astrophysical research.

Exact Solutions

A table of exact solutions of the Einstein field equations consists of the following:

| Non-rotating | Rotating | |

| Uncharged | Schwarzschild | Kerr |

| Charged | Reissner–Nordström | Kerr–Newman |

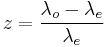

The more often used exact equation for gravitational redshift applies to the case outside of a non-rotating, uncharged mass which is spherically symmetric. The equation is:

, where

, where

is the gravitational constant,

is the gravitational constant, is the mass of the object creating the gravitational field,

is the mass of the object creating the gravitational field, is the radial coordinate of the point of emission (which is analogous to the classical distance from the center of the object, but is actually a Schwarzschild coordinate),

is the radial coordinate of the point of emission (which is analogous to the classical distance from the center of the object, but is actually a Schwarzschild coordinate), is the radial coordinate of the observer (in the formula, this observer is at an infinitely large distance), and

is the radial coordinate of the observer (in the formula, this observer is at an infinitely large distance), and is the speed of light.

is the speed of light.

Gravitational redshift versus gravitational time dilation

When using special relativity's relativistic Doppler relationships to calculate the change in energy and frequency (assuming no complicating route-dependent effects such as those caused by the frame-dragging of rotating black holes), then the Gravitational redshift and blueshift frequency ratios are the inverse of each other, suggesting that the "seen" frequency-change corresponds to the actual difference in underlying clockrate. Route-dependence due to frame-dragging may come into play, which would invalidate this idea and complicate the process of determining globally agreed differences in underlying clock rate.

While gravitational redshift refers to what is seen, gravitational time dilation refers to what is deduced to be "really" happening once observational effects are taken into account.

See also

Notes

- ^ See for example equation 29.3 of Gravitation by Misner, Thorne and Wheeler.

- ^ General Relativity

Primary sources

- Michell, John (1784). "On the means of discovering the distance, magnitude etc. of the fixed stars". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: 35–57.

- Laplace, Pierre-Simon (1796). The system of the world (English translation 1809). 2. London: Richard Phillips. pp. 366–368. http://books.google.com/?id=f7Kv2iFUNJoC.

- Soldner, Johann Georg von (1804). "On the deflection of a light ray from its rectilinear motion, by the attraction of a celestial body at which it nearly passes by". Berliner Astronomisches Jahrbuch: 161–172.

- Albert Einstein, "Relativity: the Special and General Theory." (@Project Gutenberg).

- R.V. Pound and G.A. Rebka, Jr. "Gravitational Red-Shift in Nuclear Resonance" Phys. Rev. Lett. 3 439–441 (1959)

- R.V. Pound and J.L. Snider "Effect of gravity on gamma radiation" Phys. Rev. 140 B 788–803 (1965)

- R.V. Pound, "Weighing Photons" Classical and Quantum Gravity 17 2303–2311 (2000)

References

- Misner, Charles W.; Thorne, Kip S.; Wheeler, John Archibald (1973-09-15 1973). Gravitation. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-0344-0.